On Christmas day, 2015, I went to the theater to see Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Key on every viewer’s mind was the question of why The Force Awakens seemed to have the exact same plot as A New Hope, the first of the original Star Wars movies, released in 1977. This essay will assert that the near-identical plot in The Force Awakens is not mere laziness, nor heavy handed fan service. Instead, it is in deference to the political moment from which Star Wars originally emerged – in particular, it revisits the tension between two different interpretations of Modernism, and more pointedly, two different interpretations of the violence Modernism necessitated. It also addresses the astounding, swiftly growing divide between the democratic government and the democracy that began at the end of the Cold War. Finally, with the Jedi, it asks what a moral geography that did not advantage one space at the expense of another would look like.

In the United States, early in the 1970’s, the zeitgeist itself began to resist both forms of violence, and turned instead towards privatized interests to represent them. By the 1990’s, the line between public and private was substantially blurred, and Bill Clinton was deregulating Wall Street. Between 1970 and the turn of the century, there were three crucial developments: first, and perhaps most importantly, a growing divide between the people and their government – where the sixties and seventies had been a time of protest and political movement, after the end of the cold war, the zeitgeist turned against the legitimacy of American governance. Secondly, and as a result, we saw the rise of neoliberalism which placed its faith in the free market instead of government, and we also saw the emergence of its cultural analog, postmodernism. Thirdly, and finally, the rapid development of information technologies in partnership with free market ideologies that were not statist, and could be sometimes even anti-statist, led to an increasing awareness of a lopsided globalization, in which certain nations were disproportionately disadvantaged in the “world system” that arose alongside Modernism.

The divide between the people and their government is key in the comparison between A New Hope and The Force Awakens – this divide allows Modernist tensions to play out between warring entities on the political field, and postmodernist, neoliberal, globalized (kill me now) tensions to play out in the lived experience of the citizenry of the galaxy. It is on the ground that the most pertinent question is being asked: what does it mean to be sentient? In this way, neither the New Republic, nor the First Order have anything to say to the people – democracy or not democracy is not the question, it is Heidegger’s question that is asked again and again in the deserts of the Star Wars galaxy: what does it mean to be?

**

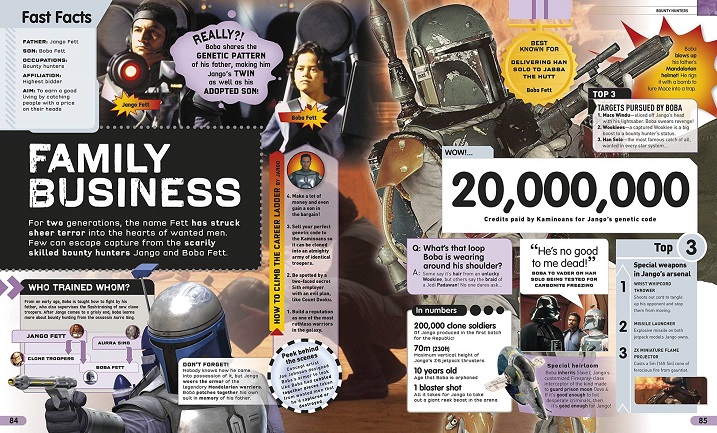

Consider that there are three interests in A New Hope: the first is that of the Empire, which is interested in maintaining and solidifying its dominance; the second is that of the rebel alliance, fighting on behalf of the Republic to overthrow the Empire ostensibly in order to achieve better representation in governance; and the last is that of the Jedi, whose order is not allowed any sort of national loyalty, and who therefore mainly fight on behalf of moral geographies. The last case is special, in that it is not purely ideological, nor purely spatial – the Jedi uniquely protect particular moral-spatial relationships, according to its own principles and not those of any other political party or power. This lends itself to a kind of religious tribalism, in which Jedi exist simultaneously inside and outside of whatever location they physically (literally) inhabit. In A New Hope, the Jedi Order has long been extinct, but it begins to make a revival via Luke and his (then unbeknownst to us) sister Leia, who are the first in a long time to be particularly sensitive to the Force, the primary tool of the Jedi. To suggest the Jedi approach some kind of true universalism would be as foolish as suggesting that the process of globalization does not also ignore or destroy particular geographies and populations.

As previously discussed, postmodernism emerges in the 1970’s. Intertwined with it are post-structuralism and deconstructionist modes of thought and expression. These projects together with neoliberalism dismantled many of the political structures that were meant to preserve national interests in favor of individual freedom, guaranteed by the market and its quantitative forms of measurement. That is to say, freedom became synonymous with “the free market,” and left behind the confines and context of the state. Neoliberalism has come under sustained critique for engendering a globalization process which promotes ideological discourses that exclude particular geographies and populations, or literally uses them as trash receptacles for the world’s literal garbage (the latter being an environmentalist critique about structural violence). This ideology proposes that justice is an entity that is derived from a combination of competition and contracts. In this case, the social contract is the same thing as the commercial contract, and it is competition that allows the commercial contract which is the most just to dominate. For neoliberalism, the market is the great equalizer because its judgment is amoral and in fact not even qualitative; it is rationalism’s secularism. The Jedi represent the extreme opposite: they are not secular (although their spiritualism is not monotheistic), and they are, essentially, moralists. The dark side is composed of people who do things that are morally corrupt, often simply to prove their own moral corruption. Although this is, in many ways, the opposite of rationalism, the Jedi mythos shares one important thing with the neoliberal mythos: it claims universalism, while in fact being essentially Western.

Alongside the Jedi (and their implicit criticism of neoliberal approaches to not only the present, but also world history), there are the political mechanics of nation states, representing in the Star Wars universe what we might understand as the common struggle, associated with the working class. See both Luke’s family and Rey’s. These characters, who are a stand in for the majority of the members of the Star Wars universe in terms of status and ideology, represent a more literal Westernism. In this case, “A New Hope,” might really refer to “A New Hope for the Triumph of the West,” which is synonymous with a “A Triumph of Modernism.” We can see the rebel fighters as the literal wing, and the Jedi as the ideological wing of a retelling of the Eurocentric, Western myth of modernism. You know – the one that valorizes imperialism, that wants to introduce both a logistically literal and Hegelian-esque ideological conception of the state to the world, thereby advancing us all into the global destiny we deserve: one of peace and prosperity, but also notably one of gentility. (Hegel’s conception of the state is rather confounding to me, but apparently he saw the “state” as an advancement in rational thought, and not anything remotely material). Given the timing, A New Hope might have been better titled, “A Dying Hope.”

**

In fact, The Force Awakens (spoilers – but really if you haven’t seen it yet, then…) opens in the globalized desert foreseen by critics of neoliberalism. In this universe, the middle class has disappeared, leaving behind a wealthy class, an impoverished class (scavengers), and a pervasive black market, where a droid’s worth in food rations is often seen as more valuable than his agency or sentience. There has been a failure to resurrect the Jedi. This failure was marked by obscene violence, which is contrasted in this movie with a certain kind of violence that is valorized. It is, after all, Luke’s light saber that calls to Rey. The tension between these forms of violence – the one the heroes use and the one the villains use – plays out inside Kylo Ren, son of Leia and Han. With the Jedi disinherited by all sides, the First Order rises to challenge the New Republic. The First Order understands itself to have global jurisdiction.

“It is the task of the First Order to remove the disorder from our own existence, so that civilization may be returned to the stability that promotes progress. A stability that existed under the Empire, was reduced to anarchy by the Rebellion, was inherited in turn by the so-called Republic, and will be restored by us. Future historians will look upon this as the time when a strong hand brought the rule of law back to civilization.“ – Kylo Ren

The New Republic also sees itself with global jurisdiction.

This is democracy… We will not always get it right. We will never have it perfect. But we will listen. To the countless voices crying out across the galaxy, we have opened our ears, and we will always listen. That is how democracy survives. That is how it thrives…That is the New Republic.“―Olia Choko[src]

Both of these are deeply modernist constructions, and one is obviously meant to also remind us of fascism. The First Order sees civilization as a product of carefully calculated, meticulously executed violence. A civilized society is an ordered society, where individuality and individual expression are devalued, and order is maintained through fear. The New Republic, when it valorizes to the messiness of democracy, is talking about a different kind of violence – not the kind that one brings to bear on the world to maintain order, but the kind that one is called to despite order. The New Republic has no army, because it relies on this different form of violence. That is the rebels, who use violence to disturb order. The explicit reference to listening is also notable, the New Republic premises its modernist conception of freedom on the right to be heard. This was represented in real world Western Modernism as well, but it was illusory – there were numerous populations whose voices cried out and who were silenced. But both the First Order and the New Republic are modernist insofar as each takes a primarily Western view of what civilization entails and applies it broadly, which is understood as the ethically correct course of action — as opposed to a pragmatic or contractually ensured course of action.

But these two major forces are waging war over a galaxy that is largely composed of people who are not interested in anything but themselves and perhaps, at most, their own families. Between these two conceptions of Modernism, and these two kinds of violence, there is a tension that still rests almost entirely in the ideological sphere – it comes down to ideas and ethics. Meanwhile, on the ground, the people and other sentient creatures we see in the Star Wars universe seem to be interested in neither order, nor being heard. They are interested in survival, and though the faint echoes of civilization as something greater than the sum of its parts emerge from time to time, they largely conceive of government as being essentially carceral – restraining and containing. This final tension, in which value is judged, at its most abstract, contractually is the one that most resembles our lived reality in the United States today. It is the extras in Star Wars: The Force Awakens that represent 2016, and postmodernism, and neoliberalism. In Rey, and Finn, the millennials (kill me now) in The Force Awakens, we also see an anguish that arises due the constant and fierce struggle to develop identity in this brave new world. They are concerned throughout The Force Awakens, not with the fate of the New Republic at all, but with their own fates, of what they mean to mean.

Meanwhile, above the zeitgeist, an ideological struggle over governance plays out.

**

Above and below, the Jedi are simultaneously missed and dismissed, and with them, the notion of moral geography. Both the First Order and the New Republic see the galaxy in terms of territory. This is most obvious when the First Order destroys the New Republic with a physical weapon in physical space. Yet the Jedi believed in a system that did not recognize nationalism as a priority or a measurement of value. Their system also relied on ethical measurements and not contractual or pragmatic ones. The Jedi experiment failed, allegedly because Kylo Ren, who stood between two sides of the Force, snapped. But perhaps the truth is that the Jedi experiment cannot work for precisely the same reason that globalization is not just; the illusion of universalism is itself a form of oppression, and will always fall apart under the pressures of nationalist interests. The Jedi Order can only exist in a world where the ideology of universalism doesn’t come at the expense of whole nations, who are ultimately exempted from this “universalism” exactly in order to make this “universalism” possible. This pits nationalism against universalism, and it was Modernism that gave nationalism its ethical underpinnings.

What results is a world in which national interests play out at a high level, disenfranchised citizenry involve themselves in pragmatic interactions based around survival at a lower level, and the Jedi project remains undeveloped. It could be argued that the world needs to become ready for the Jedi, and it could be argued that the Jedi need to do that work themselves; what cannot be argued is that the Modernist tensions, and the kinds of violence inherent to them, are not threatened nor made irrelevant by globalization, or any self-proclaimed universalism. The real threat to modernist tensions comes from the alienation of the citizenry, and their movement towards neoliberal, postmodern modes of living.

Hey Dylan,

Hey Dylan,